Section 8 Karim Doesn’t Want You To Read This

Last updated: August 2025

The online real estate influencer known as “Section 8 Karim” (aka Karim Naoum) has made repeated fraudulent and malicious attempts to silence legitimate questions I raised about his business model in an article I published last year. He seems quite desperate that the article in question, which his prospective customers are finding online while trying to learn more about him, not be found at all.

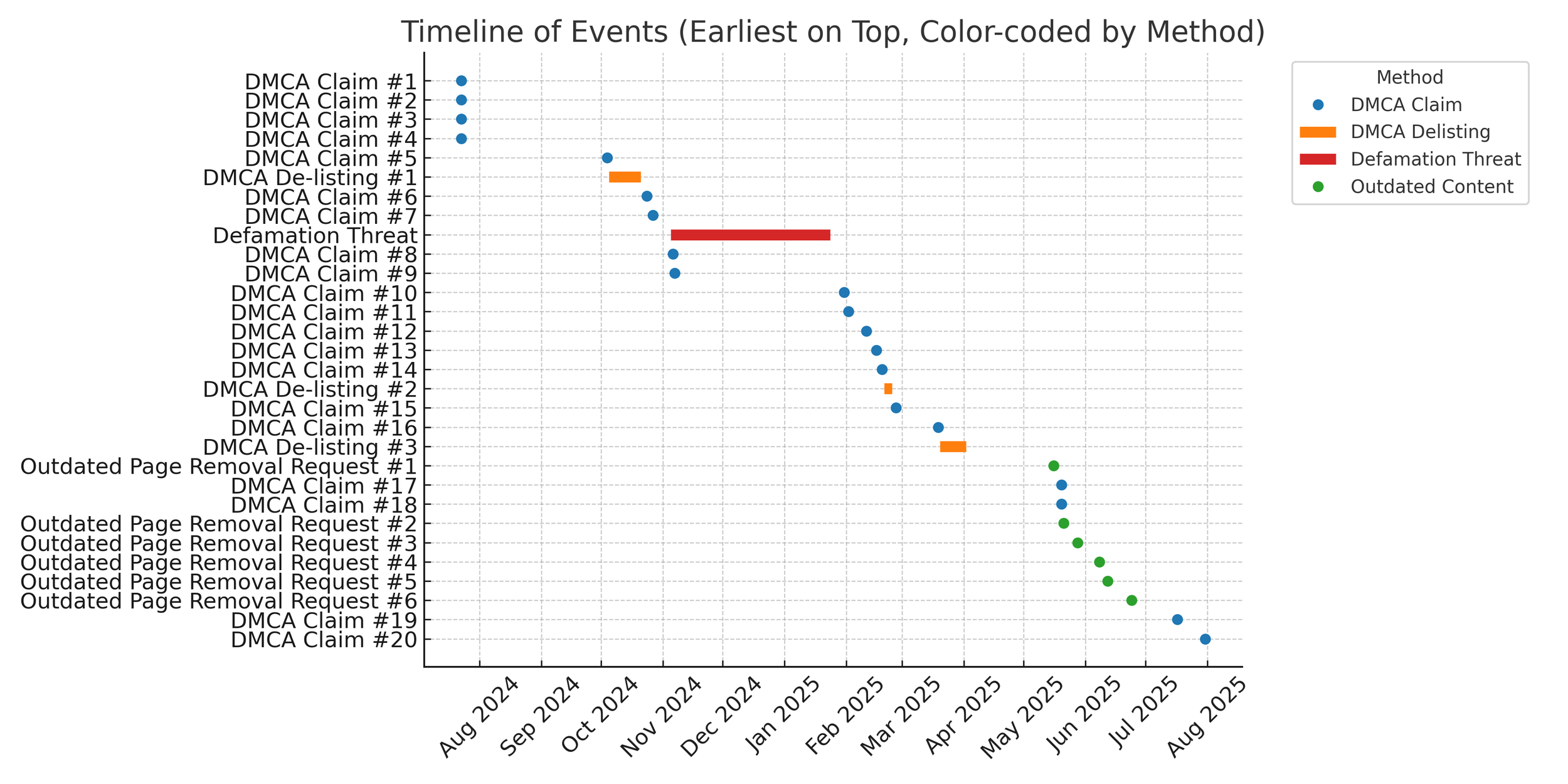

Karim — or someone acting with his interests in mind — has used three different methods (so far) in their efforts to erase this article from the public record:

Submitting fraudulent copyright infringement claims under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA)

Threatening to sue me for defamation

Abusing Google’s “Remove Outdated Content” tool

In this article, I will provide all the details about these numerous efforts to silence me and remove this article. It’s a sad story that illuminates the dark underbelly of digital reputation management, and the lengths to which some people will go to control and distort what you can find about them online.

Before I get into each of these three methods, let me provide the brief backstory of how I learned about Karim, and why I wrote the article in the first place.

The Backstory: My Introduction to Section 8 Karim

If you’re a first-time reader, a bit about me: I am a reformed retail executive turned real estate investor, writer, and coach. I own 25 rental properties in the Memphis area, and transparently publish detailed information on how they perform on this blog. I used the cash flow from these properties to leave my retail career in 2019 at the age of 39, and since then have been a private coach to over 100 aspiring investors looking to build similar cash flow portfolios. I focus on “the real deal”: I aim to be as straightforward, transparent, and honest as possible in my coaching and published content so that new investors have appropriate expectations. I take my role as a publisher and a coach very seriously, and work extremely hard to give both my readers and my private clients valuable, reliable guidance.

Back in the early summer of 2024, I began to hear the name “Karim” repeatedly in my initial coaching consultations with prospective clients. I wasn’t familiar with him at the time — most of his presence is on TikTok and Instagram, platforms I don’t spend a lot of time on. After I heard his name mentioned for the third time, I was curious enough to do some digging, watch some of his videos, and take a look at his Section 8 training program.

In my opinion, and based on my experience, the promises he was making (and still is making) to investors about Section 8 rentals were overinflated and misleading. I wrote the article to closely examine those lofty promises, mostly so that if future coaching prospects had also encountered him and asked me for my opinion, I could point them to the article and say, “that’s what I think.”

To my surprise, the article quickly began to draw organic traffic from Google searches, presumably from people searching online for information or opinions about Karim and his program. (I periodically check those kinds of site traffic statistics using tools provided by Google; people primarily find me through my blog content showing up in online search results, so it’s an important part of my business.)

But then, less than two months after I published the article, organic traffic suddenly dropped to zero and stayed there. Here’s a graph of clicks and impressions by day over that period:

To be clear, this is NOT a normal pattern. Once an article starts getting impressions and clicks, there may be some fluctuation over time due to other articles being published, changes to Google’s search algorithms, etc. — but it never drops off a cliff to zero. Clearly, something had caused the article to stop appearing in search results ENTIRELY.

Unfortunately, I didn’t notice this until about a month later. The article was still available, and still indexed by Google — in other words, links to the article weren’t broken, and you could still navigate to the article from my blog and read it. But the article was being completely suppressed from appearing in search results. Even when I googled the full url, or pasted an entire paragraph from the article into the search bar, it would not appear in the search results.

I was dumbfounded. At the time, I had no idea what mechanism inside Google could even cause this. Of course it occurred to me that Karim himself might prefer the article not be found…but what could he have done? I assumed Google wouldn’t simply suppress my article because Karim complained about it. Maybe he claimed successfully that I had violated some kind of Google policy with the article?

I had no idea, but it all felt wrong to me. About a month later, I decided to re-publish a lightly modified version of the article under a new url, so that Google could again find it, index it, and have it appear in search results. (This is the same version of the article that is currently published.)

As you might have already guessed, the same thing happened again: after gaining some initial momentum, the article dropped to zero impressions and clicks. The only difference was that it happened much faster this time, only a few weeks after publication:

Dumbfounded all over again, I redoubled my efforts to figure out how this was possible. Could I really be prevented from publishing my personal opinion about Karim Section 8’s claims, and have that published content be found through online search? This seemed insane to me, and downright un-American.

Eventually, I solved the mystery: Google had “de-listed” my article because of a copyright claim against it. Which brings us to the first method Karim (or someone acting on his behalf) has used in his efforts to scrub this article from the internet: fraudulent abuse of a law called the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA).

Method #1: Flood the zone with fake copyright claims

The DMCA was passed in 1998 to address copyright issues in the digital age. In a world where it’s extremely easy to copy, paste, and re-publish copyrighted material online, enforcement becomes much more challenging. A key aspect of the DMCA is the “takedown notice” process, which allows copyright holders to notify online service providers (such as Google) about infringing material and request its removal.

Unfortunately, lawmakers failed to foresee the unintended consequence of this “takedown process”: rampant abuse by parties seeking to shut down legitimate online speech they don’t like.

The “backdated article” scheme

Find something online that you’d like taken down? Here’s how to (ab)use the DMCA to do just that:

Copy the entire text of the article you want removed, and publish it under a new url. This is typically done inside a shell site created for the express purpose of housing this stolen content. It’s nice if the site looks legit, but as we’ll see, it’s not critical.

Backdate the stolen article. This makes it look like it’s actually YOUR content that you published first, which was subsequently stolen by the true original author.

Submit your DMCA claim. This is pretty easy to do on your own — in Google’s case, they have a simple webform you can use. But what if you don’t want the complaint to contain your name or the name of your company? As we’ll see, there is a vibrant cottage industry of companies that will manage and submit DMCA claims on your behalf, including with the use of fake names and fake companies under which to file the complaints.

Importantly, the platform receiving the request has no obligation to determine whether the copyright complaint is valid, or who the rightful owner of the material truly is. But they might be liable if they fail to remove content that does, in fact, infringe on copyright. So they (generally) do the simplest possible thing: they immediately take down material that has ANY complaint made against it.

According to the law, the owner of that material can then file a counter-notice if they believe the material was incorrectly removed. Platforms like Google also facilitate these counter-notices, which leaves the two parties at a stalemate. The original claimant then has two weeks to file an ACTUAL copyright complaint in a court of law. If they fail to do so, the platform is absolved of liability, and can safely republish the material.

This might all seem sort of reasonable so far. But keep in mind that the law does not require platforms to NOTIFY owners of content that there has been a copyright claim made against it, nor that the platform has removed or restricted access to that material. Google does have a process to send these notifications via email, but I found it to be spotty and unreliable — in fending off multiple DMCA claims, I was sometimes notified by Google, and sometimes not. When notification failed, it was up to me to realize that the article had been de-listed from search, so that I could file my counter-claim.

And “targeted” is the right word to use: my article about Section 8 Karim has (so far) been the subject of 20 separate DMCA complaints. Fortunately, a nonprofit called Lumen maintains an online database of all such claims, which allows them to be researched. Here’s a copy of one of those 20 complaints — in fact, it’s the one that resulted in Google de-listing the current version of my article for the first time:

To summarize: a company called “Zerrick Corp” based (somewhat surprisingly) out of Algeria has filed a claim with Google that my article has copied their content. They provide the url from the “Merlin News Gazetta” which they claim was the original content.

Other than Algeria being a real country, all of this is completely made up. As far as I can tell, Zerrick Corp is a not a real company, there is no “Merlin News Gazetta”, and the article they provide was quite obviously copied from my site, and not the other way around. You can check out their bogus url yourself (still active at the time of this writing). Or you can watch this quick tour around the “Merlin News Gazetta” website — if it weren’t so insidious, it would be pretty hilarious:

This was just one of the 20 DMCA complaints targeting my article. In the other 19 takedown requests, fake companies from Mexico, India, Pakistan, the UK, Algeria, and Mauritania all alleged to have previously published this same article, and claimed that I had “copied” their content. Those disparate “companies” from all over the globe somehow — miraculously! — used the EXACT same wording in their DMCA claims. This was the precise text included in 16 of those 20 complaints:

“The infringing news website, has blatantly disregarded copyright law by replicating our entire original work. This includes both the meticulously crafted written content, readily available on our website, and the accompanying imagery. Despite our repeated attempts to reach an amicable solution, (hereinafter referred to as "Infringer") continues to distribute this content illegally, without our consent, and in complete violation of Google's copyright policies. We demand the immediate removal of this infringing material from Google search results to safeguard our intellectual property.”

The impact of fake DMCA requests

These copyright claims resulted in the article being de-listed from Google Search three different times so far (or four times in total if we count the originally-published version of the article.) Each time, I was forced to file a counter-notice and wait for Google to notify the make-believe “claimant” of my counter-claim before eventually reinstating the article. You can see the impact of these de-listings on the graph below: each time, for a period of days or weeks, impressions and clicks dropped to zero as Google suppressed the article from search results.

Zooming out for a minute: the problem of fraudulent DMCA claims is of course not limited to my little corner of the internet. In fact, it’s a global epidemic that is raging completely out of control. Plenty of others — bloggers, YouTubers, and legitimate news organizations — are the targets of these attacks every day. Submitting the takedown requests is extremely easy, and is often automated, but it is difficult and time-consuming to defend against these attacks. Frustratingly, the perpetrators of these illegal schemes almost never face consequences of any kind.

The net result is this: a copyright law meant to protect original content in the digital age has been devastatingly weaponized AGAINST original content.

Couldn’t Google do something about this? It sure seems like they could do better. At the very least, they could develop a “whitelist” process whereby content that has been targeted by a bogus DMCA claim would be protected from all future ones. (It is maddening and nonsensical that this scheme to remove my article succeeded not once, but three different times.) It also seems that Google could also put ID verification in place for those submitting DMCA claims, which would completely change the game.

Still, Google does face some challenges here. Partly thanks to how easy it is to abuse this system, the volume of requests is enormous: Google now receives about 2 billion DMCA removal requests annually, or about 3,800 every minute. A staggering majority of those are bot-generated and pertain to non-existent or non-indexed urls, and even those that aren’t bot-generated are rarely legitimate: way back in 2009 when the volume of DMCA claims was tiny by comparison, Google stated that 57% of requests received to that point were from businesses targeting their competitors. A study using the Lumen database in 2022 found overwhelming evidence of widespread and coordinated use of the “backdated article” scheme by those looking to suppress negative online information, disrupt investigative journalism, or even cover up crimes. Google may be trying to combat the fraud here, but it’s clear from my experience and that of many other people that they are fighting a losing battle.

Zooming back in to my particular situation: it should be obvious by now that behind those 20 DMCA claims, invented companies, and shell domains is a single unnamed entity whose aim is to prevent people from seeing my article. I don’t know for sure who that entity is — possibly it’s Karim himself, or more likely a reputation management company working on his behalf — but what IS clear is that someone out there really doesn’t like this article, and the most likely person to dislike the article is Karim himself.

In other words, it seems implausible that this is a coincidence — especially when you consider what was happening in the period between the 1st and 2nd de-listing in the graph above, from November 2024 to February 2025: that’s when Karim threatened to sue me for defamation.

Method #2: Threaten a defamation lawsuit

Once the backdated article scheme had twice failed to permanently remove the article from Google Search, Karim turned to a new strategy: the threat of a defamation lawsuit.

To be clear from the outset, nothing in the article is remotely defamatory. The article reviews the public claims that Karim makes, and provides my personal and professional examination of those claims. This, very clearly, is constitutionally protected speech — at least as far as this non-lawyer understands such things.

On November 5th, 2024, just a few weeks after Google reinstated the article and the 1st de-listing ended, I received a cease-and-desist letter from a law firm representing Karim demanding that I take down the article. I was confident the article was not defamatory, and the threat seemed unserious in a few other ways. First, the firm in question was The King Firm out of New Orleans, a personal injury firm with no experience in defamation law. Second, because my company is New York-based, the letter referenced alleged violations of New York State law — but I was able to learn that the firm’s lawyer was not licensed to practice law in New York. Therefore, it wasn’t clear how he would actually file suit even if he wanted to.

Despite all that, this kind of threat gets your attention. I thought it best to hire a lawyer and provide a full response, both to cover all my bases and also to convince Karim that I was serious about defending myself against his attacks. I hired a NY-based firm with a specialty in defamation law. Responding to Karim’s threat in this way came at significant personal cost to me — good lawyers aren’t cheap.

For legal reasons, I won’t describe any discussions that may have taken place between the lawyers. In the end, the article remained published, and unchanged.

The last note from my lawyers was sent in late January. Then, predictably, the bogus DMCA claims resumed on January 31st, 2025 after a 3-month hiatus that directly coincided with the defamation threat. One DMCA claim filed on February 19th resulted in the 2nd de-listing from Google Search; another one filed in March caused the 3rd de-listing. And they haven’t slowed down — as of the last update of this article, the most recent DMCA claims were filed on July 31st, 2025.

Most of these DMCA claims, however, do NOT result in Google taking action against the article — there have been three de-listings so far, out of 20 claims submitted. I don’t have visibility as to why, but presumably Google is able to see (sometimes) that the claim isn’t valid for one reason or another, and doesn’t action it.

So Karim — or someone acting with the same goal to erase this article — have recently turned to a third tactic: abusing Google’s “Remove Outdated Content” tool.

Method #3: Claim that the content is “outdated”

Having batted away numerous bogus DMCA complaints, I knew the process well: I had to check my traffic stats often, and if I saw them drop to zero, I would have to file a counter-claim to Google in order to get the article re-instated.

This happened again on May 18th — or so I thought. I filed the counter-claim, but Google responded to say that they hadn’t de-listed the article due to a copyright claim. (The Lumen database confirmed this, which I hadn’t even bothered to check because I had just assumed that this was yet another fake DMCA complaint.)

So I was seeing the same impact on the article, i.e. it was not appearing in Google search results, but it was NOT the result of a copyright claim. This led me down another long path of online research to figure out what OTHER mechanism might be used by a malicious actor to suppress content in this way.

Eventually, I figured it out. Google provides something called the “Refresh Outdated Content” tool. The idea is to allow a fast method for Google search results to be updated when a page’s content has changed. Of course, Google will eventually recrawl the page, notice that the content has changed, and update search results accordingly — but this can take many weeks or even months. If you don’t want to wait that long, you can use the Refresh Outdated Content tool to speed up the process.

A user from Google Community forum provides a great example of the legitimate use of this tool:

“My name appears on a google search in which the article no longer exists and has been deleted by the posting party. However the google search title still appears and shows my name. I have submitted 3 “content removal” request on 3 separate times and they all get approved and end up expiring. I was told that at some point google will delete the search result but I am wondering when this happens? I’ve been waiting for months and the result is still there.”

This seems quite reasonable. Obviously, though, the potential for abuse is significant, as this thread on Google’s support forums illustrates. There, the user is describing the same exact issue with this tool’s abuse by malicious actors who want specific urls removed from Search. In essence, anyone can unilaterally get ANY url de-listed by claiming it is “outdated” — all you have to do is submit your request using this easy web form that Google provides. The Google rep in that support thread claims that’s not how it’s supposed to work, and that they’d look into it…but that was 2023, and clearly no changes have been made because I’m now facing the exact same problem.

Just like with the DMCA requests, it seems that Google does not have a rigorous internal process to distinguish legitimate requests from abuse. The first request on May 16th had been approved by Google, despite the page not being “outdated” in any way. The approval of this “outdated content” request was what caused my traffic to drop to zero in mid-May.

Also like the DMCA requests, there is no reliable notification method from Google to content owners when a removals request is filed. (We get confirmation emails for EVERYTHING these days, but not this?) So it’s up to the owner of the content to notice that something has changed in their traffic, or check the Removals section of the Google Search Console directly.

Fortunately, once you see the malicious actor using this method, it’s very easy to resolve: as the webmaster/content owner, I can simply cancel the removal request with a few clicks, and the article is immediately re-listed.

I have now had to do that SIX different times:

For three of these requests, I noticed them and canceled them before Google could approve them, so there was no impact.

But in the other three instances — the requests on May 16th, May 21st, and June 8th — Google approved the removal requests quickly enough that there was some impact on search results, creating brief periods of zero traffic to this article:

Summary of the Full Timeline

Taken together, it’s easy to see that there has been a coordinated effort to attack this article using various methods:

I want to be crystal clear on one thing: while I know for sure that the defamation threat came from Section 8 Karim, I can’t be 100% sure that he is behind the other malicious attacks. However, common sense and the timing of these various activities strongly suggest that he is.

And unfortunately, I’m not the only one being subjected to these tactics. Several other content creators — such as Troy Kearns on YouTube — have also seen their content targeted in similar ways. My guess is there have been many others.

Final Thoughts

Believe me when I tell you that I had absolutely no desire to take a deep dive into the dark underworld of how the internet REALLY works, and the ways in which malicious actors can abuse its systems to control what you can and cannot see. I’d much rather write about rental property investing. But I was forced into it by the myriad incoming attacks on my original content, the lifeblood of my business.

I have no personal animus toward Section 8 Karim. I have differences of opinion with him about real estate investing, and the returns that investors should expect. We should each have the ability to make our arguments, and let investors judge who is more credible, experienced, and honest in a free and open marketplace of ideas.

But it’s foul play to attempt to silence contrary points of view and “delete” content you don’t like from the internet. It’s cheating. It corrupts and warps that open marketplace of ideas, and tilts it towards those who are willing, in the name of “reputation management”, to abuse systems actually meant to protect — such as the DMCA, defamation law, and Google’s outdated content tool.

I personally would not trust or do business with anyone willing to do that.

About the Author

Hi, I’m Eric! I used cash-flowing rental properties to leave my corporate career at age 39. I started Rental Income Advisors in 2020 to help other people achieve their own goals through real estate investing.

My blog focuses on learning & education for new investors, and I make numerous tools & resources available for free, including my industry-leading Rental Property Analyzer.

I also now serve as a coach to dozens of private clients starting their own journeys investing in rental properties, and have helped my clients buy millions of dollars (and counting) in real estate. To chat with me about coaching, schedule a free initial consultation.